Cattle and Cowhands

the rural roots of farm life in Missouri

(originally published March 21, 2019)

Heaven is fields of grazing cattle- at least it is for the farmers who call Missouri home. The endless cattle dotting Missouri’s countryside have a unique role in rural life. Ranking in at number three in the nation for beef production, Missouri’s history, culture, and economy is shaped by its roots in the cattle industry. Despite its seemingly quaint appearance, agriculture is no minor operation. It is an $88 billion industry in Missouri with nearly 100,000 farms across the state. Cattle account for a significant portion of this industry and their role is at the centerfold of discussion as the debate over the future of the food system continues to progress.

The traditions and institutional importance surrounding cattle farming are well known to Cord Jenkins, a lifelong Missouri resident and agricultural educator.

“I have been around cattle my entire life. My grandpa had a farm that I called our family farm. As my grandpa got older, my dad took over that farm and I worked on it throughout my entire childhood,” Jenkins said.

Multigenerational farming is a common thread within Missouri’s cattle industry. The state’s natural aptitude to grow forage has allowed for a long history of farmers to integrate cattle into the state’s identity. As agriculture and rural areas have traditionally been closely intertwined, cattle are often viewed as synonymous with rural culture. While rural life is no longer solely dependent upon agriculture for its economy, the importance and appreciation of livestock continues to holdfast.

“Part of that stems from proximity and also from the roots and development of Rolla,” Jenkins said. “Rolla is the biggest community in the area and serves a whole bunch of rural areas. It was built on agricultural values to begin with. The roots of those people are still here. I think that’s what makes Rolla, a city of 20,000 people, still pretty darn rural.”

Jenkins now manages his own farm of 60 cattle with his wife and daughters. His farm is a cow-calf operation- the most common method of raising cattle in Phelps County where a permanent herd of cows is kept to produce beef calves for later sale.

“When you talk about Missouri and Phelps County beef producers and how they feel about their beef herd, people take it very very seriously. For one it is a huge financial investment, but it’s also part of your blood,” Jenkins said.

It is clear from Jenkins that raising cattle is more than just a livelihood, but a way of life. Similar sentiments are echoed across the agricultural community, including within Jenkins’s own classroom. Brody Brown is a junior at Rolla High School who is the President of the local Future Farmers of America (FFA) chapter. Similarly to his peers that have grown up immersed in farm life, Brown has a strong connection to cattle.

“I think it was a great place to grow up and I’d like to raise my kids on a farm, but then also I just think it’s important to have farmers and rural values,” Brown said.

Brown lives on his family’s farm south of Rolla where he helps tend for a cow-calf operation of 100 “mama cows.” Like most kids on a beef cattle farm, Brown started his work on the farm feeding his own bottle calf. His duties have grown since then: he feeds the herd daily, gives hay in the wintertime, chops ice when it’s frozen, and checks up on the cows and calves.

“Working on a farm would make anybody more responsible because you know there are lives you have to take care of and keep alive, not only for profit but for their wellbeing. It takes a lot of hard work and a good work ethic to keep them healthy,” Brown said.

For Brown and other family farmers, taking good care of their livestock is as ingrained in their farm practices as any other factor of production. Cow-calf operators raise their cattle primarily on pasture, rather than grain feeds, and have more land than other cattle operations. Once male calves are weaned from their mothers, they may be sold to a backgrounder who will continue to prepare the cow for production, or they can be sent directly to feedlots. Feedlots are the final step before slaughter where cattle are fattened with grain in a smaller, enclosed environment. This common step in beef cattle production is where the industry meets the most opposition, including calls for entirely grass-fed beef.

“This is where within agriculture, sometimes we butt heads. What I teach my kids is that we in agriculture are one family and we have to understand that there’s room in the market for all people,” Jenkins said.

While the market does consists of multiple viewpoints, aversions to the food system’s shift towards industrial agriculture, commonly referred to as “factory farming,” grow stronger in America. Factory farming is defined as “a large industrialized farm; especially: a farm on which large numbers of livestock are raised indoors in conditions intended to maximize production at minimal cost.” The application of the term factory farming to the beef industry is hazy and not all-encompassing. While poultry and hog farming has largely been taken over by corporations, cattle farms remain almost entirely family-owned. According to the United States Department of Agriculture 2012 census, 97 percent of all U.S. farms are family-owned. However, farms are characterized as “factory” based upon the amount of livestock they produce, not by their ownership. Although cattle farms have a broad range in size, from small herds to giant operations, the largest producers still hold the highest concentration of production.

The cattle industry, as a whole, can also have a negative impact on the environment, particularly through greenhouse gas emissions and land usage. However, the values and natural ties held by most farmers do not necessarily conflict with sustainability goals.

“The better I take care of my land, which is a huge value that most agriculturalists hold very true to their heart, the better it’s going to produce and grow forage and then the better off I’m going to be for growing beef,” Jenkins said.

The potential for cattle to have negative impacts on Missouri’s land is inescapable. There are 28 million acres of farmland in Missouri, compared to the state’s total land area of 44 million acres, of which only 14 million acres is forest land. As farms account for over half of Missouri’s land, the health of the land used in cattle farming is critical. Rick Cowlishaw is a professor at Southwestern College in Winfield, Kansas who has worked with various natural resource management agencies to promote land and resource preservation. Cowlishaw specializes in the intersection between agricultural practices and the environment.

“Typically, farmers that farm small amounts of acreage are really connected with their land,” Cowlishaw said.

The connection between farmers and their land is critical in Cowlishaw role on the board supervisors for his county’s Soil and Water Conservation District. Soil and Water Conservation Districts, which are present under Missouri’s Department of Natural Resource, incentivize farming conservation practices that relate specifically to grazing management and keeping livestock out of streams. This attempts to offset the major environmental effects that runoff, pollution, erosion, and habitat loss have as a result of cattle. While the effects of land management practices can be seen and understood at a local level, cattle’s impact on the broader issue of climate change requires more widespread awareness.

“There is a growing group of farmers that are realizing that the farm system that has been in place is broken and that changes need to be made if we want to continue to grow the food that we are going to need in the future, but also do it in a way that works by the rules of nature,” Cowlishaw said.

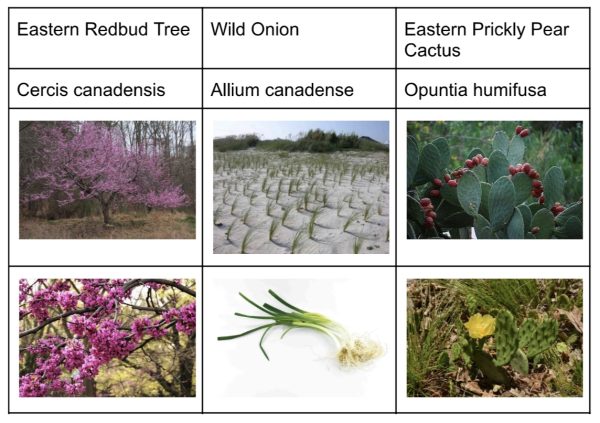

The United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change published a report in 2018 revealing that livestock accounts for 14.5 percent of total global emissions and that beef is responsible for 41 percent of livestock greenhouse gas emissions. These greenhouse gas emissions come from: methane from cattle and their wastes, energy utilized to produce feed crops and general farm production, and land usage. Tree and plant cover has the ability to capture and store carbon from the atmosphere in the soil, but the land used to produce cattle and grain can lose this ability. Cowlishaw advocates for farming techniques that could improve carbon storage, such as no-till farming, planting cover crops, agroforestry, and composting. These farming practices would allow land to have regenerative, carbon capturing qualities, while still being utilized for agriculture.

“Just as agriculture is part of the problem, they’re also part of the solution. Farmers are rethinking the way they grow food and how by working with soil we can best achieve this,” Cowlishaw said.

Agricultural choices can be made by these inclusive standards: the ecological health of the farm and the economic health of the farmer. The value of cattle’s contributions towards traditional culture and livelihoods needs to be part of the discussion as the food industry continues to progress to meet the needs of the American people.

“I think a lot of people within the agriculture industry don’t realize, not that it’s a bad thing, it’s our fault if anybody’s, how far away the general public is from agriculture,” Brown said.

No matter in what way the industry manifests itself, the public’s diet is still based off of the backs of individual farmers.

“One story that my great grandpa always told is that he grew up farming with horses, his son grew up farming with open station tractors, and his great-grandsons were farming with tractors that drive themselves. Just in his generation that much changed, so there’s no telling what could happen in the next generation,” Brown said. “There’s still a lot of things that, even with as many advancements in technology that we have, haven’t changed for hundreds of years. The base is still the same as it always has been.”

Regardless of the future of the cattle industry, the culture and values surrounding farming should guide it’s path.

“I think the family farm has just changed with time to stay vibrant and alive. I don’t see the family farm going away from the agricultural landscape. It’s the backbone and soul of American agriculture,” Jenkins said.

Hello! I’m Lauren and I’m super excited for my first year in Echo. I’m a junior this year, and I’m involved in band, debate, eco club (you all...