Neat steel cameras hang from lush crochet straps, small and digital off a dozen students’ necks. Scratched black Walkmans droop out of sweatpants and cardigans, bygone wired gods of decades half-forgotten. Somewhere in a third-floor classroom, a girl hits Record on her Chromebook, peeking past its grimy face, and wishes the pixelated world a warm welcome to her vlog.

These scenes mark a keen technological adaptation—and, arguably, evolution. Amid a flurry of yellowed card games and ’90s electronics, Rolla High School has changed. On July 9, Missouri Governor Mike Kehoe signed Senate Bill 68 into law—a brand-new policy that, throughout all statewide public and charter schools, enforces the absolute prohibition of student cell phone use during every class, meal, and break.

This policy ricocheted into effect on RHS’s first day of school, hurling a blanket ban over all personal electronic devices from 8:00 AM to 3:10 PM. Junior Mya Watkins was caught in the tide.

“I actually heard about the new phone ban just three days before school started, so I was in shock … I was kind of like, ‘Dang, that’s crazy,’” Watkins said.

The new policy has struck rippling effects across campus, tumbling against students from all walks of life.

“Actually? I thought that everyone was just gonna go against the rules and do what they wanted, use their phone whenever they wanted, but everyone loves the new phone ban. My friends do, at least, and I do as well, because it makes us more in touch with our peers and teachers. I think it makes us look at life a little bit differently. Definitely, everyone’s more social now. No one has no one,” Watkins said. “There’s still people that go into their groups and don’t talk to anyone else, but I’ve made more friends this year because of the phone ban. I think that a lot of other people might be a little bit mad, but I think this is a good way to get people out of their shell.”

To Watkins, the ban offers new spaces to breathe and thrive within the student body.

“It just feels like everyone’s more alive. I’ve talked to more people that I don’t usually talk to. The only thing I don’t like about it is that I love making TikToks with my friends for the memories in school. I used to do that all the time, and now I can’t, but that’s okay. I make Chromebook vlogs now. I love making Chromebook vlogs,” Watkins said.

Junior Ashton Stoney, meanwhile, felt a bit more ambivalent about the ban’s implementation. “To be honest, I didn’t think they were really gonna enforce [the ban] … but I’m quite surprised. I was doubtful that it was really gonna be so strong of a presence, but now that we’re here, I see how it’s changing our culture here at Rolla High School,” Stoney said.

The new law has banished an omnipresent digital shroud, leaving students with no choice but to pay attention to the tangible and the physical.

“A lot of my friends used to play Brawl Stars, and that used to be a big social group gathered around video games. It brought people together in many ways. Now, they don’t really have that way to socialize with each other, but, because of that, they have more verbal conversations,” Stoney said. “Before, when we were bored, we used our phones as a way to entertain ourselves. Now, I feel like we’re using other methods; maybe more reading, maybe more socializing. Especially in our generation, it’s harder to just talk to people one-on-one without the distraction of phones. So I feel like this [policy] might help us break down the middle man, which is the internet.”

In short, with one hand, the phone ban takes away fistfuls of digital asylum; with the other, it proffers cupped palms of human liveliness.

“I definitely feel a lot less distracted, a lot more engaged in class. I also feel like I have less communication, though. Overall, I think I’m changing for the better,” Stoney said.

RHS faculty can confirm that, without phones, their students have begun to learn more effectively.

“[Before the ban], I would lose two to even three minutes an hour per class just to get the class settled down and off their phones,” Jacob Rinehart, high school history teacher, said.

Evidently, this is no longer the case. Freshman Selena Eckert reflects similar sentiments coupled with a few observations of her own.

“I heard about the phone ban maybe a few days before school started. But I originally came from St. Pat’s, where we weren’t really allowed to have our phones. So I was okay with it because I was used to that,” Eckert said.

Eckert feels the ban only puts a temporary pause, though, like a light switch that flips back on the moment the 3:10 PM bell rings.

“What I don’t like is that whenever school is over, we’re always just back on the phone. A lot of students have this separation anxiety during the school day,” Eckert said.

Senior Chase Wilkins is particularly affected by the policy due to his age.

“I probably heard about the new phone policy in later July, and my initial reaction was, ‘Wow, what a way to start my senior year.’ … I know it has affected me more just because the younger kids back in the junior high weren’t allowed to use their phones anyway,” Wilkins said.

Though his social life has remained largely unchanged, Wilkins believes the phone ban slows down the more practical parts of school.

“It hinders some school productivity. There were some times where I needed to get pictures or stuff off my phone or text my parents, but couldn’t. And class is a little bit different. Not being able to have access to our phones for research and all sorts of stuff like that makes schoolwork harder during school,” Wilkins said.

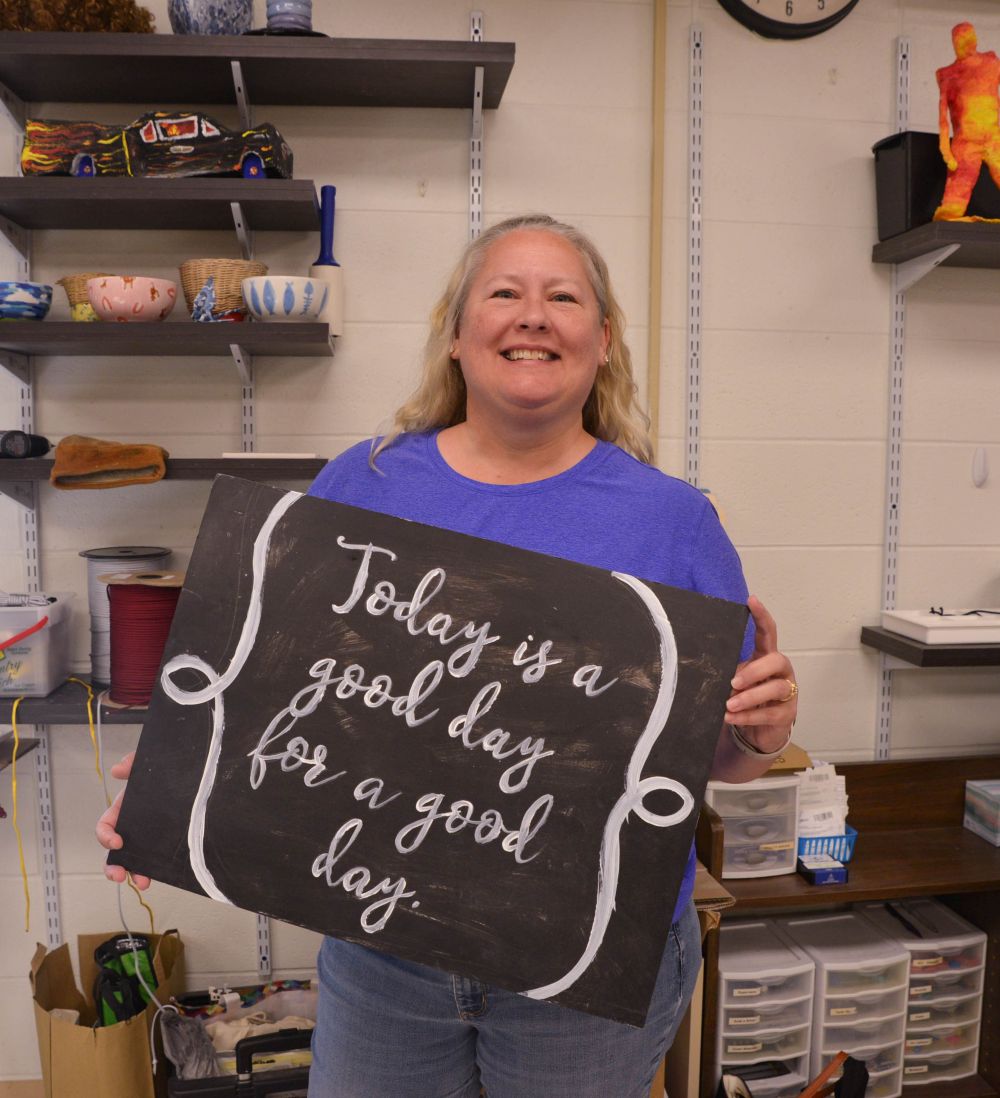

Behind the scenes, administrators have had to prepare for the policy since mid-summer, overseeing RHS’s total switch from personal devices to school Chromebooks. Peggy Borrock, RHS library paraprofessional, lives at the heart of this shift.

“The Chromebook cabinet—where students will bring in their Chromebooks that need repairs or go to borrow a loaner for the day—that’s mostly in the library now. For the first couple of weeks, as everybody’s learning how to use the new system, as we’re figuring out the glitches with tech, I think there’ll be a learning curve to figure out how to make it work,” Borrock said.

Borrock has contemplated the totality of the ban and its effectiveness.

“We’re teaching kids to be in the world, whether that’s work or college. When you leave here, you don’t have those same restrictions, necessarily. Is it better to teach students how to do that responsibly versus eliminating it altogether? That’s a question that I don’t know I have the best answer to,” Borrock said. “I believe it will settle once everybody knows how it works. The reduction in distractions in the classroom will be good for students. I think we just don’t need to be that connected twenty-four hours a day. And I’m guessing the ban is here to stay.”

Dr. Corey Ray, principal of RHS, agrees with Borrock about preferring some leniency to teach students responsible device management. He also points out that the policy is not black-and-white.

“We do have kids that need access to their phone during the school day because they may not know where they’re going to be sleeping that night because they got kicked out of their house. There’s never a one-size-fits-all [policy] that works for everybody,” Ray conceded.

Watkins, Stoney, Eckert, and Wilkins all stated that, if given the opportunity to change any one thing about the phone ban, they would choose to allow phones during students’ lunch hours. Small mercies, they agree, might calm the bitterness rising among some students and grant a much-needed window for communication, recreation, and digital refreshment.

Though the policy grants phone usage during extreme emergency situations and has allocations made for special circumstances, it is still stricter than the school-specific phone ban Dr. Ray enacted in previous years, which only banned devices in classrooms—and was simply a school policy, not a state law.

“With the current ban, now that you have the law to back you up, it puts a little more teeth into it. Right now, things are different than they were last year. Kids are interacting more for sure. They’re playing card games in the cafeteria now, where you wouldn’t have seen that a year ago. I’ve heard of kids investing into the old Walkman, which is interesting, because those things were out when I was a kid maybe one hundred years ago,” Dr. Ray said.

Dr. Ray is hopeful about the future of the policy and the high school.

“We’ve had very few incidents with electronic devices … I’m so very proud of the kids and grateful to the parents for their support. By and large, what I’m hearing across the state is better than people expected,” Dr. Ray said. “I hope it creates a distraction-free environment where kids are enjoying interacting with one another. If the beginning of the school year is any indication of the path that we’re heading down, it’s going to be a better school environment.”

Interviewing support from student journalist Kaidence Sneed.